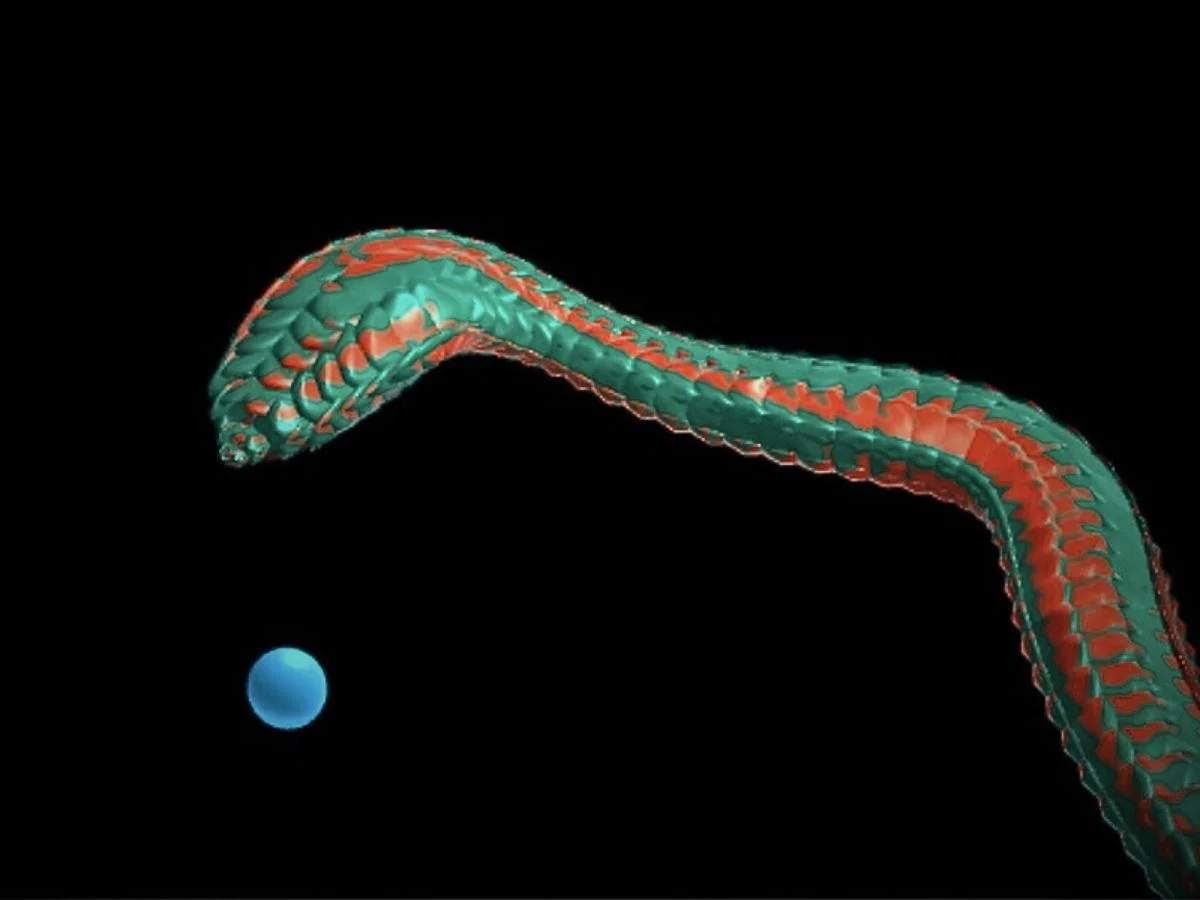

Imagine a snake slithering across the screen, smoothly chasing your mouse along an organic path.

Building that path is the challenge. Mouse input is noisy, motion must update in real time, and the curve can’t be precomputed or stored ahead of time.

1. Introduction

This tutorial introduces a two-part curve system to solve it. CurveGenerator produces short cubic Bézier segments steered by behavioral rules, while EndlessCurve stitches them into a continuous, memory-bounded path. With that in place, we render a procedural snake on top.

Inspiration

While looking at retro Snake games, I wanted to reimagine the idea in 3D by removing grid-based movement and replacing discrete steps with smooth motion. The result turned out to be more complex than expected, so let’s dive right in.

2. Generating the curve

Each curve segment begins with a single question:what direction should the snake move in now? That direction isn’t picked outright. Instead, it emerges from several small steering impulses blended together, arguing politely until one wins.

Each update follows the same pattern: first we decide on a desired direction, then we constrain how fast that direction is allowed to change, and finally we turn the result into a short Bézier segment. The rest of this section walks through how that direction is chosen.

Steering the direction

The motion is driven by a force-based model inspired by Craig Reynolds’Steering Behaviors(for background reading, see this link and this link). Rather than simulating multiple agents, we treat the snake as a single entity that blends several behavioral impulses into one direction vector.

The forces we combine are seek, orbit, coil, wandering, and turn-rate limiting. Individually they are simple, but together they produce motion that feels intentional rather than mechanical.

Seekpulls the snake toward the target when it’s far away. A small buffer helps avoid rapid switching as we approach the orbit zone.

if (dist > orbitRadius * 1.5) {

desiredDir = targetDir

}Orbittakes over when the snake gets close. Instead of charging straight in, we compute a tangent direction around the target (a 90° rotation on the ground plane), which makes the snake circle at a roughly constant distance.

const tangent = new Vector3(-targetDir.z, 0, targetDir.x) // perpendicular on XZ plane

const radiusError = dist - orbitRadius

const radialStrength = radiusError * 0.1

desiredDir = coilTangent.clone().addScaledVector(targetDir, radialStrength).normalize()Coiladds a vertical component while orbiting, producing an up-and-down motion. The height follows a sine wave, and the direction follows its derivative, which keeps the movement smooth rather than jerky.

const coilY = coilAmplitude * coilFrequency * Math.cos(coilFrequency * orbitAngle) * coilActivation

const coilTangent = new Vector3(tangent.x, coilY, tangent.z)

desiredDir = coilTangent.clone().addScaledVector(targetDir, radialStrength).normalize()Wanderintroduces subtle variation so the motion doesn’t look mechanically perfect. Real animals don’t move in perfectly straight lines. If they did, they’d look suspicious.

Two independent noise samples rotate the direction horizontally and vertically. Rather than replacing the direction outright, we blend the resulting delta in at a low weight:

const wander = wanderForce(lastDir, noise2D, noiseTime, wanderStrength, tiltStrength)

const wanderDelta = wander.clone().sub(lastDir)

desiredDir.add(wanderDelta.multiplyScalar(wanderWeight))Finally, we apply aturn-rate limiter. No matter what the forces decide, the snake can only rotate bymaxTurnRateper segment. This constraint is what keeps the motion smooth and prevents the snake from instantly changing its mind and folding back on itself.

function limitTurnRate(current: Vector3, desired: Vector3, maxRate: number): Vector3 {

const angle = current.angleTo(desired)

if (angle <= maxRate) return desired.clone() // small change, use as-is

if (angle < 0.001) return current.clone() // near-identical, skip

const axis = new Vector3().crossVectors(current, desired)

// ... handle degenerate parallel/anti-parallel case ...

axis.normalize()

return current.clone().applyAxisAngle(axis, maxRate)

}

const newDir = limitTurnRate(lastDir, desiredDir, maxTurnRate)From direction to curve

Now we have a direction. Time to make a curve. Each update produces a short cubic Bézier segment.

The endpoint is simply the previous point advanced along the new direction (no surprises here):

// endpoint

const endPoint = lastPoint.clone().add(newDir.clone().multiplyScalar(length))The control points decide how much the curve is allowed to bend. Their distance scales with how sharply the direction changed: short handles for straight motion, longer ones for tighter turns (because sharp corners are rarely a good look):

// control points

const turnAngle = lastDir.angleTo(newDir)

const turnFactor = Math.min(1, turnAngle / (Math.PI / 2))

const controlDist = length * (0.33 + 0.34 * turnFactor)

const cp1 = lastPoint.clone().add(lastDir.clone().multiplyScalar(controlDist))

const cp2 = endPoint.clone().sub(newDir.clone().multiplyScalar(controlDist))

const curve = new CubicBezierCurve3(lastPoint, cp1, cp2, endPoint)This adaptive range was chosen empirically. It keeps the curve smooth without overshooting. After a few failed experiments, it turns out restraint helps.

To keep segments joining cleanly,

cp1follows the previous direction andcp2follows the new one. This preservesG1 continuity, meaning each segment leaves in exactly the direction the previous one arrived.

Generating individual segments solves local smoothness, but the snake’s body moves continuously. To manage that,EndlessCurvetreats multiple segments as a single, continuous path.

3. Infinite curve

We need a system that treats multiple Bézier segments as a single continuous path by generating new segments ahead, removing old ones behind, and keeping the snake’s orientation smooth and twist-free along the way.

The sliding window

The snake’s body is just a window moving along an ever-growing path. Every frame, it advances forward by a small amount:

this.distance += delta * this.config.speed

this.curve.configureStartEnd(this.distance, this.config.length)configureStartEnd()handles the bookkeeping. It ensures there’s enough curve ahead, removes anything that’s fallen behind the tail, and updates a local[0, 1]parameter space representing the visible portion of the snake:

configureStartEnd(position: number, length: number): void {

this.fillLength(position + length) // generate ahead

this.removeCurvesBefore(position) // trim behind

const localPos = this.localDistance(position)

const totalLen = this.getLengthSafe()

this.uStart = totalLen > 0 ? localPos / totalLen : 0

this.uLength = totalLen > 0 ? length / totalLen : 1

}As the window moves forward, new curve segments are generated only when needed. Each segment is short (4–8 units), so in practice this usually means adding one or two curves at a time, just enough to stay ahead of the motion. While other segments that fall completely behind the tail are removed.

Even though old curves are removed, the global distance counter keeps increasing.distanceOffsetbridges the two, allowing the rest of the system to continue working in global coordinates without needing to know that cleanup is happening.

Once the sliding window is configured, the path is remapped into a local[0, 1]space, where u=0 represents the tail and u=1 represents the head.

getPointAtLocal(u: number): Vector3 {

return this.getPointAt(this.uStart + this.uLength * u)

}Extracting normal

In addition to the curve itself, we need a stable reference frame. Choosing the wrong one leads to visible twisting artifacts.

To place geometry on the tube surface, the vertex shader constructs an orthonormalTBN frameat each point along the spine. The tangent is straightforward; the normal is where things tend to go wrong. A poor choice causes the cross-section to rotate unpredictably, making the body appear twisted.

A common approach is to project a fixed world-up vector:

N = normalize(up - T * dot(up, T))This works while the curve stays mostly horizontal. When the tangent aligns with the up vector, however, the projection collapses and the frame becomes unstable.

The solution isparallel transport. Instead of computing frames independently, the normal is propagated forward along the curve by applying the same rotation that aligns the previous tangent with the new one. This produces a stable frame with minimal twist.

Parallel Transport Frames

private parallelTransport(

prevNormal: Vector3,

prevTangent: Vector3,

newTangent: Vector3

): Vector3 {

const dot = prevTangent.dot(newTangent)

if (dot > 0.9999) return prevNormal.clone()

const axis = new Vector3().crossVectors(prevTangent, newTangent).normalize()

const angle = Math.acos(Math.max(-1, Math.min(1, dot)))

const rotated = prevNormal.clone().applyAxisAngle(axis, angle)

rotated.sub(newTangent.clone().multiplyScalar(rotated.dot(newTangent)))

return rotated.normalize()

}This producesminimum twist: the frame rotates only as much as the curve itself requires. No additional spin is introduced unless the path physically demands it, such as in a full helical turn.

Frame caching

Parallel transport is sequential: each frame depends on the previous one. To make random access efficient, frames are precomputed and cached at fixed samples along each Bézier segment.

When a frame is requested at an arbitrary parameter value, the code finds the surrounding cached samples and interpolates between them:

return cache.normals[low]

.clone()

.lerp(cache.normals[high], t)

.normalize()Because the samples are close together, linear interpolation is sufficient and avoids the cost of spherical interpolation.

Cache maintenance

When old curve segments are removed, their cached frames are discarded as well and the remaining parameter values are recomputed. For the small number of active segments involved, the cost is negligible, and the frame data stays tightly bounded in memory.

With a continuous curve and stable orientation data in place, we can move on to rendering. The goal now is to turn this mathematical spine into a convincing three-dimensional body.

4. Generating the snake

Unfortunately, snakes are not lines.They are three-dimensional bodies with thickness, a tapering tail, a heavier head, subtle twists, and surface detail that really wants to catch the light.

This section focuses on turning that curve into something that actually looks like a snake, without rebuilding geometry every frame. We’ll cover instancing, and rendering methods to make it more realistic.

Building the scales

This project takes a different approach from the usual: the snake’s body is assembled frominstanced geometry, with all positioning handled in the vertex shader. The CPU samples the curve and uploads the result as textures. The GPU does the rest.

Each instance is a simpleOctahedronGeometry. When flattened and slightly overlapped, these octahedrons form a tile-like surface that reads as scales.

Building data textures

TwoDataTextureobjects carry the curve data to the GPU. The two textures serve different roles:

- Normal texture: the RGB channels store the surface normal, encoded as

value * 0.5 + 0.5to fit the[-1, 1]range into[0, 1]. The shader decodes it back withvalue * 2.0 - 1.0.

- Position texture: the RGB channels store the world-space XYZ position of each spine sample.

The updateTextures() function is run every frame to get position + normal:

for (let i = 0; i < texturePoints; i++) {

const u = i / (texturePoints - 1)

const basis = this.curve.getBasisAtLocal(u)

const idx = i * 4

posData[idx] = basis.position.x

posData[idx + 1] = basis.position.y

posData[idx + 2] = basis.position.z

posData[idx + 3] = 1.0

// Encode normals as 0-1 range

normData[idx] = basis.normal.x * 0.5 + 0.5

normData[idx + 1] = basis.normal.y * 0.5 + 0.5

normData[idx + 2] = basis.normal.z * 0.5 + 0.5

normData[idx + 3] = 1.0

}Realism

Once the body exists, the remaining work is about convincing the eye. Small anatomical cues (thickness changes, asymmetry, surface detail, and lighting) do most of the heavy lifting.

Several small effects contribute to the final look: a non-uniform radius profile along the spine, an elliptical cross-section, a subtle twist to break symmetry, and surface shading that emphasizes grazing angles and elongated highlights. Individually these are simple, but together they push the body away from a smooth tube and toward something that reads as organic.

Radius

Real snakes aren’t uniform cylinders, so the radius varies along the spine:

spineU: 0.0 --------- 0.74 ---------- 0.85 ----- 0.95 ---- 1.0

tail tip body neck head tip

[ramp up] [full thick] [pinch] [bulge] [close]Elliptical

Snakes are wider than they are tall. The cross section is modeled as a flattened ellipse rather than a circle, using a 0.5:0.8 vertical-to-horizontal ratio.

float radiusNormal = scale * u_radiusN; // vertical

float radiusBinormal = scale * u_radiusB; // horizontalFlat Belly

A small belly offset (u_zOffset = 0.2) pushes the underside outward slightly, creating a subtle ventral surface — one of those details that’s barely noticeable until it’s missing.

ringOffset += spineNormal * combinedThickness * u_zOffset;Twist

A gentle twist is applied along the spine. This breaks up visual regularity and prevents the surface from reading as a perfectly aligned grid. Real animals rarely cooperate with perfect symmetry.

float twistedTheta = theta + spineU * u_twistAmount;Normal

A subtle noise-based perturbation adds micro-scale variation to the surface normals. This breaks up overly clean lighting and helps the body catch light unevenly, as scales do in reality.

Belly Lighting

Most snakes have a lighter belly. The shader identifies the underside using cos(vTheta) and applies a multiplicative brightness boost. Because the adjustment is multiplicative rather than additive, the spot pattern remains visible (just lighter), which matches how pigmentation works on real snakes.

Lighting

Several lighting tweaks reinforce the illusion of a rounded, glossy body:

- Rim lighting(power ≈ 3.5) accentuates grazing angles, making the silhouette read clearly against darker backgrounds

- Shadow compression(

diffuse * 0.6 + 0.4) prevents the shaded side from collapsing into pure black, loosely approximating subsurface scattering - Anisotropic specular highlightsstretch reflections along the body, mimicking the directional microstructure of real snake scales

5. What’s next

Belly-constrained motion

Restrict movement so the snake always travels on its ventral side, preventing unrealistic rolling and reinforcing grounded motion.

Stricter coiling behavior

Refine the orbit and coil forces to produce tighter, more deliberate wrapping, especially during close interaction with the target.

A more anatomical head

Introduce a distinct head mesh with independent shaping, jaw definition, and eye placement, while keeping it driven by the same curve and frame system.

Environmental interaction

Extend the steering system to respond to obstacles, surfaces, or terrain, allowing the snake to navigate spaces rather than open ground.

Alternative bodies

Swap the rendering layer to create tentacles, ropes, vines, or abstract trails — the curve system remains unchanged.

6. Conclusion

This project explores how continuous motion can emerge from simple rules, without relying on predefined paths or heavyweight geometry. By generating the curve incrementally, managing it as a sliding window, and pushing most of the rendering work onto the GPU, the snake feels fluid and responsive while remaining efficient and predictable.

The real win isn’t the snake itself, but the structure around it: motion, continuity, and rendering are all handled independently, which keeps the system flexible as it grows.

The broader takeaway is the pattern itself. By decoupling motion, path management, and rendering, complex behavior can emerge from simple components. This approach scales well beyond snakes to any system that needs continuous, responsive motion without predefined paths.

What We Built

- A real-time curve system that generates smooth, continuous paths from noisy input

- A memory-bounded, infinite path built from chained Bézier segments

- Stable, twist-free orientation using parallel transport frames

- A GPU-driven rendering pipeline using instanced geometry and data textures

- A procedural snake body with scale-like structure, anatomical shaping, and physically motivated lighting